Cholesterol Control and Reduction

Cholesterol is

sterol essential to the human diet. It is essential to cell membrane

maintenance and fat soluble vitamin absorption. It is a precursor to steroid

hormones and sex hormones such as estrogen. But in excess, cholesterol can

cause hypercholesterolemia. Hypercholesterolemia is the condition of having

abnormally high levels of cholesterol in the blood. This is a strong

contributing factor to heart disease since the excess cholesterol will

precipitate in artery walls and form plaques causing atherosclerosis and

possibly turn into a stroke or myocardial infarction (Lewis and Burmeister,

2005). Heart disease is a leading cause of death in

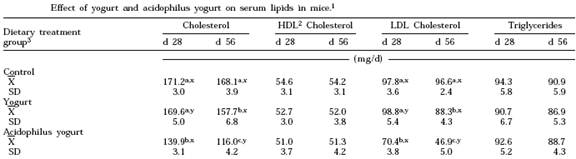

Table 2: A table of cholesterol levels at 28 day and 56 day interval of the three study groups. All groups were fed only fed commercial rodent chow and water for the first 28 days before having different regimens for the next 28 days. The control group was only fed commercial rodent chow and water. The yogurt group was fed commercial rodent chow and yogurt made from milk inoculated with Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus. The acidophilus yogurt group was fed commercial rodent chow and yogurt made from milk inoculated with Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Both non-control groups did not receive water under their regimen. (Akalin et. al, 1997)

A study, Influence of Yogurt and Acidophilus Yogurt on Serum Cholesterol Levels in Mice, examines the effects of not one, but two different strains of Lactobacillus on cholesterol levels of mice (Akalin et. al, 1997). Both yogurt groups, compared to plain water, seem to lower LDL (low density lipoprotein, bad cholesterol) significantly with the yogurt cultured by L. acidophilus being the greatest decrease as seen in Table 2. While the delbruecki yogurt group dropped the LDL about 10 mg/d on average, the acidophilus yogurt group dropped the LDL about 23 mg/d on average. By losing a third of the blood LDL in 28 days, this is the desired effect that the study was looking for and seems very promising. (Akalin et. al, 1997)

An important observation to not overlook is that for some reason, the acidophilus yogurt group started with a lower average LDL blood content than the other two groups. While this doesn’t invalidate the study, that detail does call into question the methods of the experiment. All the groups of mice seem to have experienced an average drop of 3-4 mg/d in triglycerides, which is probably due to their diet and probably irrelevant as the control experienced it too. It is difficult to draw a correlation between any of the groups’ diet and weight gain as the weight recorded on day 28 was significantly different between the control and the other groups and the weight gains seemed to increase in proportion, not by the same amount. (Akalin et. al, 1997)

Fig. 2: The graph is the change of cholesterol of the two groups over 20 days. The table shows the average cholesterol change based on milk treatment or weight at the end of the 20 days. A group of 24 male Maasai warriors were split into two even groups. They had a diet of 4-5 liters (eventually became an average of 8.33 liters) of milk a day for 5 days, followed by a meat day, and then a soup eating day were the soup is made of entrails, bones, and any other remnants of the previous day. Everything is eaten except for the brain, spinal cord, hooves, skin, and horns. The steer they ate weighed between 350-450 lbs, shared between 24 men. The two groups were divided based on the milk they drank. 12 got milk fermented by a wild Lactobacillus strain called the treated group, the other 12 got plain milk called the placebo group. (Mann and Spoerry, 1974)

A diet of only large quantities meat and milk probably sounds like a nightmare for one’s serum cholesterol and a sure path to coronary heart disease from a modern medical standpoint, but a commonly cited study has indicated otherwise. The study, Studies of a surfactant and cholesteremia in the Maasai, shows that though a life style rich in meat and milk may cause weight gain, but serum cholesterol on average decreased (Mann and Spoerry, 1974). Based on Fig. 2, a diet of just plain milk and meat apparently has significantly lowered serum cholesterol, but even better, the fermented milk doubled the results of the plain milk with respect to serum cholesterol. (Mann and Spoerry, 1974)

Another

interesting result from Fig. 2 is that those men that gained the most weight,

actually lowered their cholesterol the most compared to those who did not.

These eight that gained more than 5 lbs. stopped exercising for 2-3 hr daily

with the others after a few days, meaning they were also sedentary (Mann and Spoerry, 1974). This lifestyle

mimics the average American lifestyle of high fat diets and a sedentary

lifestyle, explaining why obesity is a national problem in

The data of this study is mediocre and the record keeping appears sloppy by today’s standards. A lot of important information was left out like who gained weight and drank the fermented milk or who didn’t gain much weight and increased in cholesterol. The scientists should make it clearer on who exercised and who didn’t as this does affect weight gain and possibly cholesterol values. They always referred to the serum cholesterol, but it would have been nicer if they found out the individual values of the HDL (high density protein, supposedly good cholesterol), LDL, and triglycerides. On the other hand, their precautions were excellent such as riboflavin markers to make sure the groups weren’t sharing their milk with each other. Another note is that the study should had been longer as the sudden increase in serum cholesterol observed in the control is worth some concern, such as if the hypocholesterolemic effects were extremely short term or if it fluctuates. (Mann and Spoerry, 1974)

Another study that investigates the hypocholesterolemic

effects of milk on Americans living a normal lifestyle is Hypocholesterolemic effect of yogurt and milk (Hepner et. al,

1979). The results shows a few analogs in to the study Studies of a surfactant and cholesteremia in

the Maasai (Mann and Spoerry,

1974). In Hepner’s study, the fermented dairy product (yogurt) and milk both

reduced serum cholesterol levels but the yogurt made a bigger statistical difference.

In the second part of the study, the researchers investigated the differences

between pasteurized and non-pasteurized yogurt. There appeared to no

significant difference between the two in terms of lowering cholesterol (Hepner

et. al, 1979). One explanation they offer

is that in this case, the intestinal flora had nothing to do with it but

something in the milk inhibited the conversion of acetate to cholesterol by

liver homogenates. They also cited a study showing that supplementing the diets

of rats with milk inhibits the biosynthesis of cholesterol, even with defatted

milk (Hepner et. al, 1979).

Conclusion

Fermentation of milk provides many benefits from culturing useful bacteria like Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus acidophilus in the war against the rotavirus threat to bringing and upgrading the potential curative properties of the milk itself. It can be seen that a little sour milk a day can cut the time of diarrhea experienced with gastroenteritis in half (Guérin-Danan et al., 2001; Isolauri et. al, 1991). A healthy baby is a happy baby, and the less time they spend suffering diarrhea, the more likely they will survive. Many options were explored from easily stored freeze-dried powders to simple-to-make raw milk cultures that can all be done anywhere where raw milk is available. Exploration of the potential of yogurt has even shown that different strains of Lactobacillus have varying beneficial effects on serum cholesterol, which is a leading problem of Americans today (Akalin et. al, 1997; Anderson and Gilliland, 1999).

The use of milk from other mammals is an indispensable commodity. And human creativity and experimentation has created many things with it from cuisine to medicine. Probiotics may not be the answer to all of mankind’s problems, but they can answer many of them without the expensive use of pharmaceuticals and lab-made chemicals.

Bibliography

Akalin S., Gonc S., and Duzel S. “Influence of Yogurt and Acidophilus Yogurt on Serum Cholesterol Levels in Mice.” J Dairy Sci, 1997, 80, p.2721–2725

Galson S.K. “Mothers and Children Benefit from Breastfeeding.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 2008, Volume 108, Issue 7, p. 1106.

Gilliland S.E., Nelson C.R., and Maxwell C. “Assimilation of Cholesterol by Lactobacillus acidophilus.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1985, p. 377-381.

Glass, R.I. “

Guérin-Danan C., Meslin J.C., Chambard A., Charpilienne A., Relano P., Bouley C., Cohen J., and Andrieux C. “Food Supplementation with Milk Fermented by Lactobacillus casei DN-114 001 Protects Suckling Rats from Rotavirus-Associated Diarrhea.” Journal of Nutrition, 2001, 131. p. 111-117.

Guerin-Danan C., Meslin J.C., Lambre F., Charpilienne A., Serezat M., Bouley C., Cohen J., and Andrieux C. “Development of a Heterologous Model in Germfree Suckling Rats for Studies of Rotavirus Diarrhea.” Journal of Virology, 1998, Vol. 72, No. 11, p. 9298-9302.

Hepner G., Fried R., Jeor S.S., Fusetti L., and Morin R. “Hypocholesterolemic effect of yogurt and milk.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1979, 32, p. 19-24.

Isolauri E., Rautanen T., Juntunen M., Sillanaukee P., and Koivula T. “A Human Lactobacillus Strain (Lactobacillus Casei sp strain GG) Promotes Recovery From Acute Diarrhea in Children.” Pediatrics, 1991, Vol. 88, No. 1, pp. 90-97 .

Kunz C., Rodriguez-Palmero M., Koletzko B., and Jensen R. “Nutritional and biochemical properties of human milk, Part I: General aspects, proteins, and carbohydrates.” Clin Perinatol, 1999, 26 (2), p. 307–33.

Lewis S.J. and Burmeister S. "A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus on plasma lipids." European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2005, 59, p. 776–780

Lorrot M. and Vasseur M. “How do the rotavirus NSP4 and bacterial enterotoxins lead differently to diarrhea?” Virology Journal, 2007, 4: 31.

Maldonado Y.A.

and Yolken RH. “Rotavirus.” Baillieres Clin. Gastroenterol, 1990 4 (3),

p. 609–25.

Mann G.V. and

Spoerry A. “Studies of a surfactant and cholesteremia in the Maasai.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1974, 27, pp. 464-469.

Pant A.R., Graham S.M., Allen S.J., Harikul S., Sabchareon A., Cuevas L., and Hart C.A. “Lactobacillus GG and Acute Diarrhoea in Young Children in the Tropics.” Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 1996, 42 (3), p.162-165.

Parashar U.D., Bresee J.S., Gentsch J.R., and

Rodriguez-Palmero M., Koletzko B., Kunz C., and Jensen R. “Nutritional and biochemical properties of human milk: II. Lipids, micronutrients, and bioactive factors.” Clin Perinatol, 1999, 26 (2), p.335–59.